Bodies wearing furniture; furniture lying on bodiesJulien Spiewak’s ‘Corps de style’ series

Jin Kwon, Independent Curator

Sometimes, our imagination of a story begins with a single scene. When we have to recall a film that is gradually fading from our memories, we take one scene that remains intact and piece together the various fragments before and after it. There are times, too, when a single name from an otherwise forgotten memory becomes the starting pointing point for tracing back to scenes associated with it. The photographs of Julien Spiewak evoke precisely¬¬ such points in our consciousnesses. All of their constituent aspects – complex elements such as structure, colour, contrast, perspective and composition of meanings and symbols – are always firmly ordered. In today’s world, where post-processing has become an indispensable part of photography, it may seem natural for photography, as a medium, to show high levels of detail. But images controlled to a degree of perfection approaching that of a master craftsman press the “stop” button and deliver their allusions at the very moment we begin imagining a story.

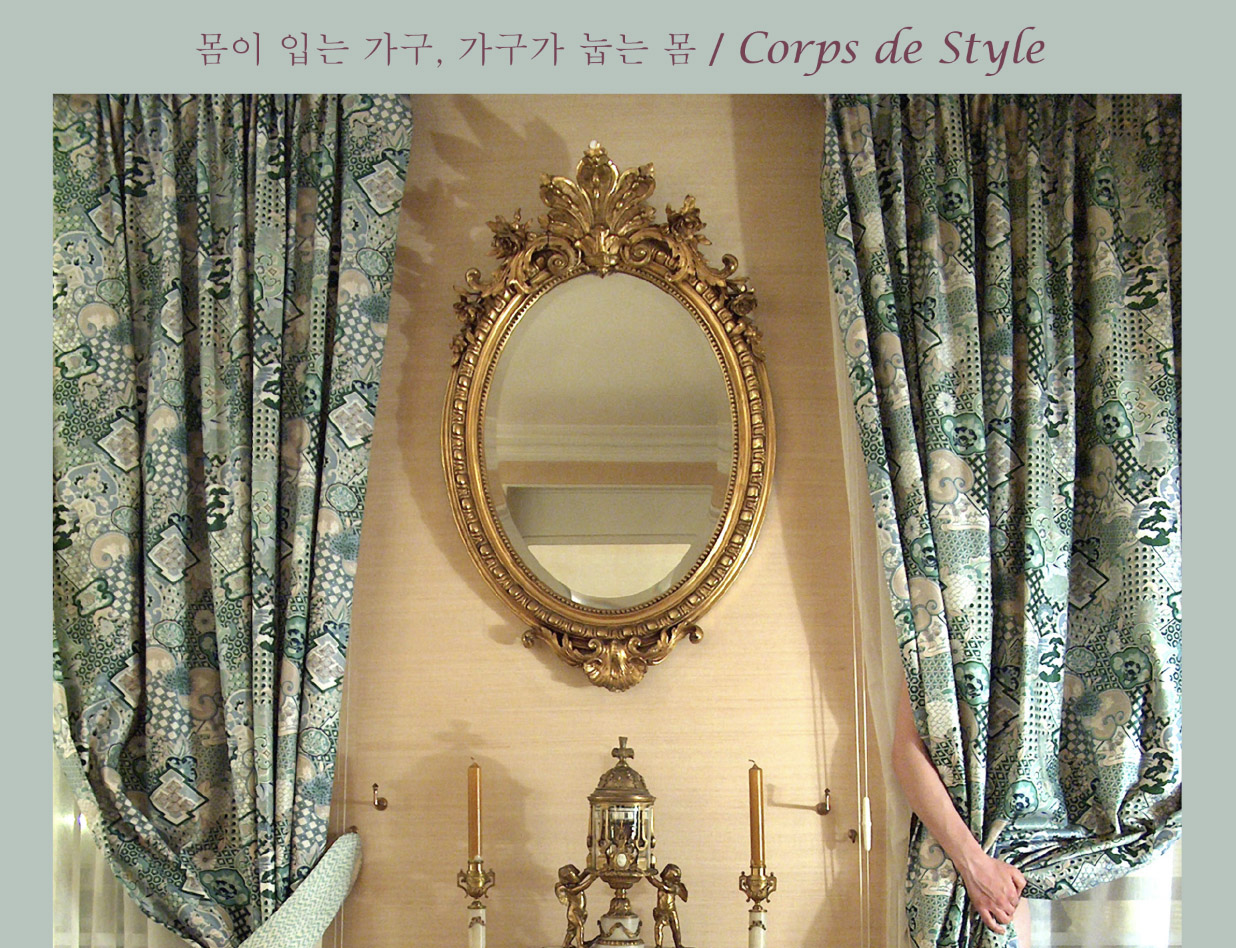

Since 2005, photographer Julien Spiewak has been making his way around antique furniture shops at Saint-Ouen flea market in northern Paris, taking photographs that address several of his interests in connection with the items of furniture he discovers. These interests go beyond mere aesthetics. Spiewak’s photographs get up close to old pieces of furniture, actively bringing in the spaces in which they find themselves and their surrounding objets, thereby expanding their meanings. The scenes he produces prompt us to imagine the “inner intentions” of each piece of furniture, including the historical character of its style and decoration, the traces of the craftsman who made it, or its previous owner. The body parts subtly inserted – not to mention perfectly positioned – in these spaces interact organically with their surroundings, creating fantastic narratives. Unlike the furniture, with its concrete information and symbols, however, these body parts set elements of performance in motion. A forearm sticking out like a curtain rod, a hand wrapped around the neck of a bust, a foot half-visible beneath a curtain or a torso hanging in a wardrobe, for example, faithfully play their role of introducing the only elements of rhythm into otherwise otherwise rigidly structured frames. At the same time, these body parts bring in expanded significance, relating to bodily perception, relationships with surroundings and temporal character. Through such precise control of situations, the artist completes his painting-like scenes.

Corps de style became truly interesting in 2012, when Spiewak began shooting against the background of interiors in the Musée de la Vie romantique in Paris. The museum houses 17th- and 18th-century portraits of French royalty and aristocracy, antique furniture used by writer George Sand, well-known as Chopin’s lover, a statue of Joan of Arc and various other works; it is a taxidermized collection of Romantic styles and scenes from the era. New works that make active use of the museum’s collection take the fantasy of the older works, which remained loyal to the interior with its antique furniture, to a new level. This time, the artist has been very direct in his demand for artistic and romantic quality. Romanticism is a definite aesthetic tendency, order and standard in European art history – a clear symbol for us to grasp. European romanticism is reproduced in so many films, so much fashion and so much culture that giving specific examples is hardly even necessary. It has become part of our culture and dominates our understanding of romance itself. As a location, moreover, a museum is somewhere that serves to reaffirm the social standing of these period pieces. Pictures that make use of the museum’s scenery, then, are powerful yet familiar, while appearing chock-full, to non-European viewers, of exotic cultural symbols. When, however, our eyes suddenly find a whole; when, in other words, we discover the body parts hidden in these perfect images, our familiar fantasies cease functioning. That is what brings us back to the present moment: one that is sensual, new and unfamiliar, and that makes us more curious than ever about the next story.

Jin Kwon, Independent Curator