Museum Van Loon (Amsterdam) – Corps de style

By Valerie Reinhold, curator

Day after day, Louise is gazing at the lady opposite her, with a quiet smile. Resting on the mantelpiece in the grand reception room, cold as marble, she has been watching day in and day out for 167 years the inhabitants, later replaced by the visitors, passing by in the Museum Van Loon. That is to say: until now. When Julien Spiewak (1984) shot her elegant portrait, he brought her back to life. The French artist, interested in the photographic medium as space to create a new reality, inserted an extraneous body, naked, that seems to stare at Louise. The painterly companion opposite the sculpture becomes a voyeur and so do we, witnessing the vitality that goes through the bare flesh flow into the whole room and radiate the marble bust. Suddenly the magic happens and we see Louise, here and now, we don’t just look at her still sculptural representation. This is precisely the intention of the artist: by creating an entirely new image where antiques and bare body parts are carefully combined, Spiewak is able to breath life, in a playful way, and to open an innovative reading of environments that have been frozen in time.

The modus operandi of the artist appealed to Museum Van Loon, who regularly hosts contemporary exhibitions in relation to their own history. “The transhistorical seems to enable a bridge between people, places and times, overcoming the gap between the two worlds by way of elevating contemporary art and democratising old masters” (The Transhistorical Museum conference, 2015). It is precisely in that context that Museum Van Loon invited Spiewak to imagine a new series of photographs in situ and in dialogue with the art, furniture, space and history of the museum. The works are part of his research “Corps de Style” (the play on words means both Bodies of Style and Stylish Bodies), developed in museum interiors and private collections around the world since 2005.

At first, the carefully constructed images may seem to be documenting the beautiful period rooms, in the footsteps of Robert Polidori’s Versailles for the framings chosen or Candida Hofer’s Libraries for the frontal view and the graphic lines. But if the photographer is inspired by the formal quality and the sober documentary aesthetics of the Dusseldorf School of Photography, he moves away from dispassion and neutrality and chooses humour and subjectivity to reconnect the viewer with a reality where past and present are intertwined. The key, hidden in the image is the body: find it and embark on a trans-temporal journey.

The artist starts by researching the space and furniture to understand their history, functionality and meaning. He then draws the period rooms or the chosen details (his sketches on view in the vitrines upstairs are exquisite) and decides how to integrate the exogenous body part that will open a new perception of the space. Spiewak explores the realm of possibilities at hand and uses the shape, texture, materiality and colour of the flesh in dialogue with the environment.

The lamp is turned on in Portrait of Willem Hendrik van Loon by Adolf Pirsch (1909), Alexandre, Louis XV commode (1760), as if someone had just left the room or was about to come back any second. The rug emphasises the “homy” feeling, however all personal items have been removed: the boundaries between the classification of the space (current museum versus former private house) are blurred. The eye is soon attracted by an incongruous element, which is paradoxically integrated in the decor: an arm, perfectly positioned, has taken over the function of the curtain loop and only differs by its materiality. The vitality of the flesh radiates to the portrait and the absent owner becomes present, again. This also happens in Double portrait of Jacob Hendrik Bode and Catharine Antoinette Boode by Johan Friedrich August Tischbein (1791), Alexandre, neo Louis XVI toilet table (ca. 1880), where an arm underlines and complements the shape of the mantelpiece. It directs our gaze towards the embraced couple and makes the love of the couple almost palpable.

In other works, Spiewak focuses on overlooked decorative elements: Jan seems amused by the hand that is holding a flower in Portrait of Jan van Loon sr. by Louis Bernard Coclers (1779), Julien; the winged woman is turning toward the hand that poking her -unless it complements her design?-, and the typical 18th century table leg is freed from her function (Giltwood Louis XIV table with marble top (early 18th century), Alexandre).

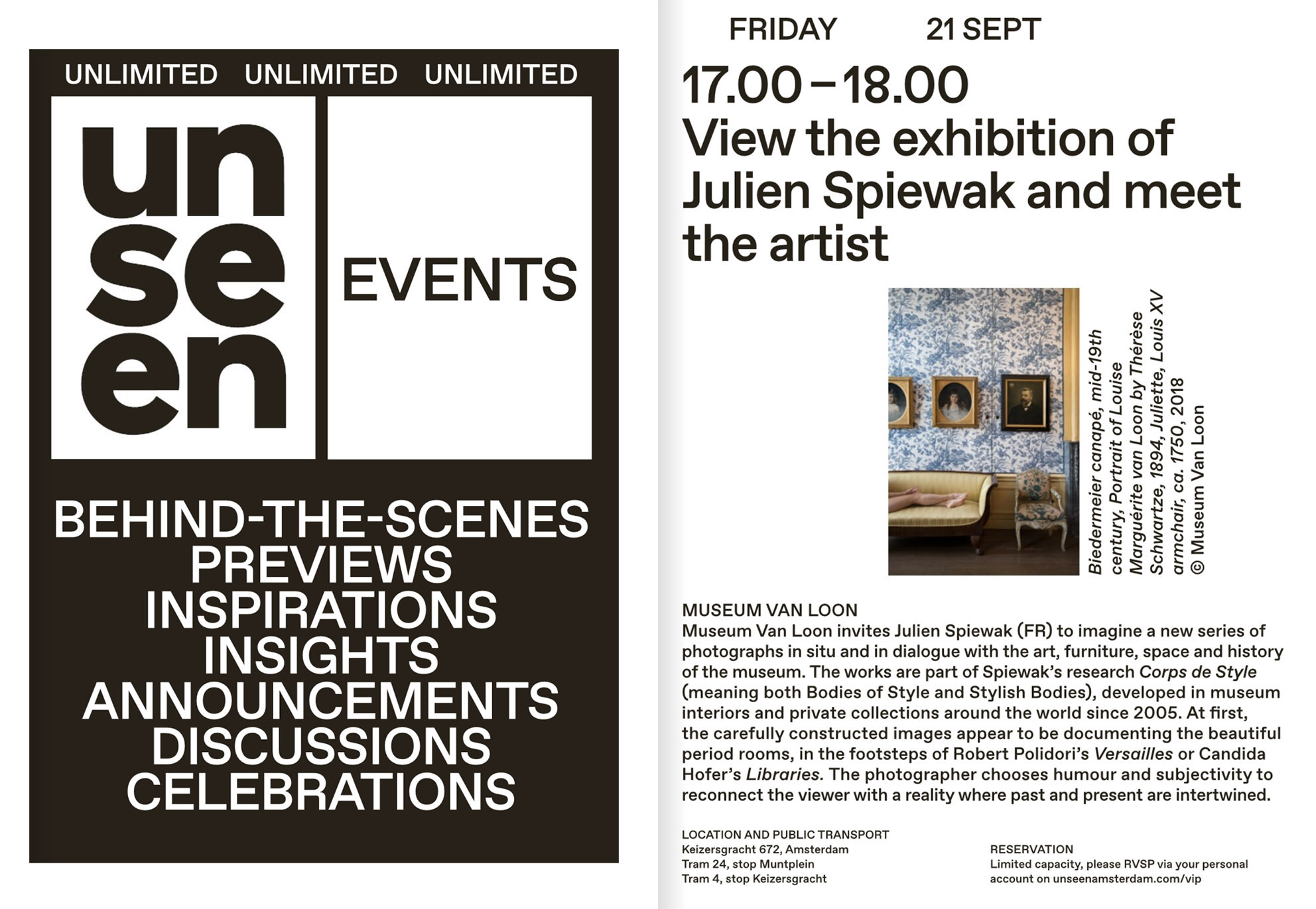

The reference can also be art historical: Biedermeier canapé (19th century), portrait of Louise Marguerite Van Loon by Thérèse Schwartze (1894), Juliette, Louis XV armchair (ca. 1750)is an homage to Madame Récamier by David.

In reaction maybe to a visual world where everything and everybody is smoothed, Spiewak is interested in obvious the traces of time, asperities and beauty spots of the flesh: its materiality opens new possibilities for dialogues with the storied space. Louis XV stair banister of Keizersgracht 672 (ca. 1750), Léopoldshows a detail of the magnificent banister. The body, though more present than the furniture, disappears and becomes material. The solid swath of colour gives way to the intricate vegetal pattern of the Louis XV banister. And once the eye is accustomed to the image, it seems that the cold metallic leaves girdle the body, infusing life back into it.

Spiewak uses the body, always cropped, in a performative way. He introduces naked models in almost sacred cultural spaces, altering the preconceived idea we have of museums, where nothing can be touched, nothing should move. By this very act he transform the visitor from a docile recipient to an active viewer. The images open new interpretations, in a similar way as One Minute Sculptures series by Erwin Wurm -where the interaction between participants and everyday object are documented photographically-, where playfulness and imagination co-exist alongside deeper meanings. Corps de Style illustrates indeed the purpose of art today, as defined by Nicolas Bourriaud: it is not destroy to rebuild but on the contrary to assess “how we can better inhabit what we inherit”. The titles are therefore important to the works: they carefully catalog the elements present including the name of the model.

The photographer acts as a catalyst: the images are activated through the eyes of the viewer. He invites us to take time, appreciate the details, feel and then discover the incongruous element for the flesh is the trigger to the transhistorical journey in Corps de Style. Objects become subjects in the enchanted space of the photographs. Anna must be happy: the reaching (and helping) hand that pulls her back into the now is her descendant, Philippa Van Loon (Portrait of Anna Ruychaver by Michiel van Mierevelt (1623), Philippa). What better way to redefine the past as being part of the present?

Spiewak’s pictures thus “challenge us, tease us for a response and push us to question our being there, our mode of looking. They invite us to think.” (Hanneke Grootenboer, (re)discovering Art History’s Philosophical Foundations, The Transhistorical Museum).

Valerie Reinhold, curator

www.redprintdna.com